SLI_Insight: How I Built a Local Expert Assistant for Electronics Failure Analysis

By Ed Hare

Consultant in Electronic Materials, Reliability, and Failure Analysis

⸻

For more than 27 years, I’ve investigated and solved quality and reliability issues across the electronics industry. In that time, I’ve seen the same problems surface again and again—often buried under too much data and too little insight.

That’s why I developed SLI_Insight, a local expert system that mirrors the way I think, work, and solve problems. It’s not just a chatbot. It’s a distilled version of my consulting methodology—integrating decades of technical experience with a structured database of real failure reports, backed by deep AI summarization.

This tool makes my expertise more accessible and more powerful for clients who need real answers, fast.

⸻

What SLI_Insight Does

SLI_Insight is a locally run expert assistant that helps identify failure causes, trace technical patterns, and retrieve key findings from thousands of archived failure analysis reports. It doesn’t rely on cloud APIs or black-box services. Everything stays local, secure, and private.

The system:

✅ Accepts natural-language queries like:

“What causes solder joint fractures on ENIG plated boards?”

✅ Instantly matches those queries to real report tags using a custom keyword index

✅ Uses SQLite to retrieve relevant sections (background, results, conclusions, figures) from prior reports

✅ Uses a local LLaMA 3.2 model to summarize the findings—grounded in real casework

✅ Outputs a clean, timestamped markdown log of the session and final summary

⸻

How I Built It

The core components of SLI_Insight reflect how I approach every consulting problem:

🧠 Knowledge-Driven Search

The system uses pre-tagged keywords and job classification data, drawn from thousands of real SEM Lab reports. Instead of relying on vague AI guesses, it retrieves failure analysis content that matches the exact technical terms you care about—cracks, CAF, ENIG corrosion, MLCC knit line failure, and more.

🧰 Structured Retrieval + SQL Logic

Each match triggers SQL queries that pull:

•The original background, results, and conclusions

•Any figure captions and image filenames

•Keywords used in the report

This structured access means I can link a symptom (e.g. “thermal fatigue”) to dozens of real-world case examples in seconds.

🤖 Local Summarization with LLaMA

At the end of each session, SLI_Insight sends relevant text into a locally running LLaMA 3.2 model for expert summarization. Unlike chatbots that “guess” answers, this summary is grounded in actual case data—something no public model can offer.

📝 Everything is Logged and Exported

All interactions are stored in a markdown file, making it easy to build reports, client updates, or technical writeups from any session. The assistant also auto-saves a standalone summary of each session’s key findings.

⸻

Why This Matters for Clients

SLI_Insight isn’t just a clever toy. It’s a force multiplier for my consulting services:

•I can find precedents and patterns in seconds, not hours

•I can trace uncommon failures back to materials, processes, or conditions

•I can deliver findings backed by data—not hunches

In short, I can help your engineering team solve problems faster, with clearer documentation and higher confidence in root cause.

⸻

Interested in Working Together?

If you’re facing yield loss, intermittent failures, or unexplained component damage—and you don’t have months to spare—I can help.

You bring the symptoms and the samples.

I bring the method, the memory, and the insight.

👉 Reach out to start a conversation.

ehare@semlab.com

SEM Lab, Inc.

Drilled Hole Roughness (Ra) as a Metric for PWB Reliability

Ed Hare, PhD – SEM Lab, Inc.

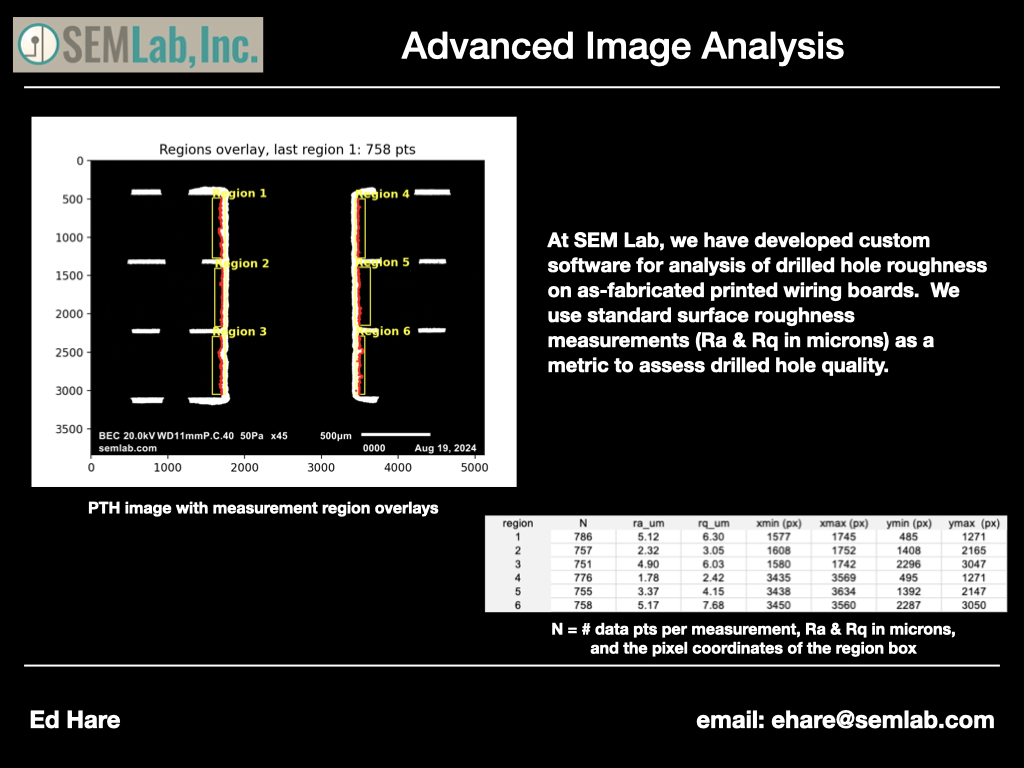

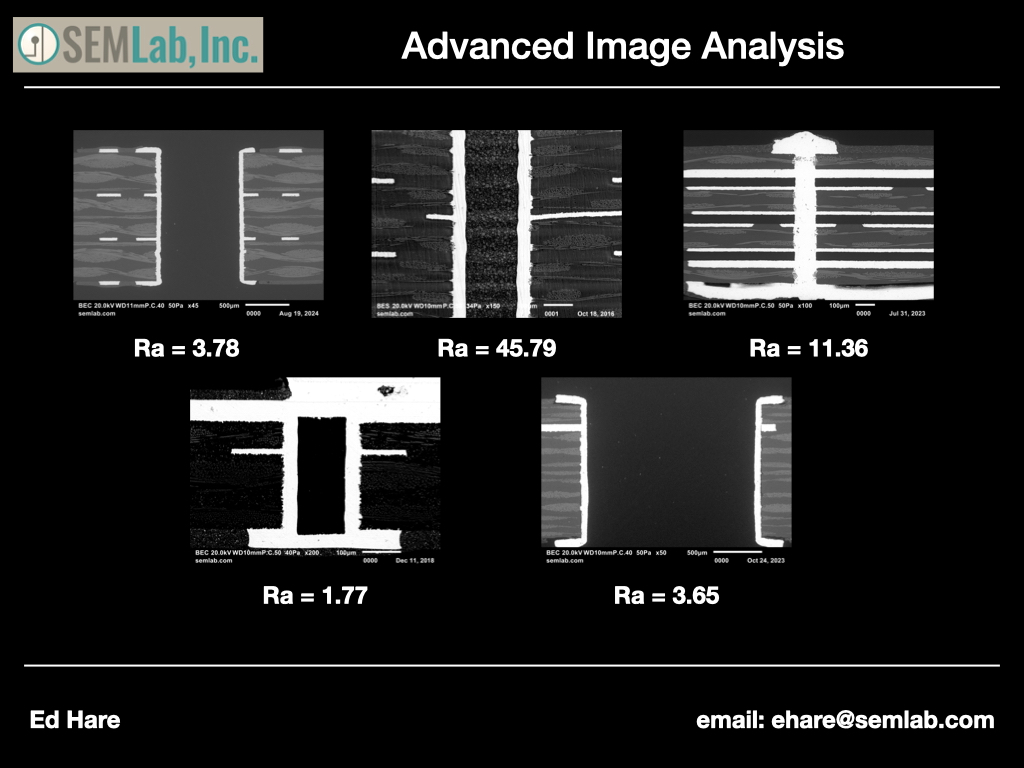

Drilled hole quality is often overlooked as a contributing factor to long-term reliability in printed wiring boards (PWBs). In particular, surface roughness of the drilled hole wall, commonly reported as Ra (arithmetic average roughness) or Rq (root-mean-square roughness), can have a significant impact on performance and failure risk.

⸻

Why Rough Drilled Holes Matter

Fabrication Indicator

Poorly drilled holes are often a fabrication quality issue—commonly related to drill bit wear, improper feed/speed, or inadequate desmear. Excessively rough drilled hole interiors are indicative of poor process control during board fabrication.

CAF Failures

Rough hole walls can create micro-crevices that promote conductive anodic filament (CAF) formation under applied bias and elevated humidity. These sites serve as initiation points for copper migration, especially in high-density multilayer designs.

Electrical Noise

Non-uniform copper topography inside the via barrel may also contribute to electrical performance variation in high-speed or RF applications. These effects are often masked during initial testing but become problematic under long-term use.

Stress Risers

Jagged or mechanically damaged areas along the drilled wall act as stress risers, which can limit fatigue life under thermal or mechanical cycling. This often results in copper barrel cracking or interconnect failure over time.

⸻

Measurement and Analysis

At SEM Lab, we use high-resolution SEM imaging and software-based analysis to calculate Ra and Rq from drilled hole interiors. Measurements are obtained from multiple regions of interest within the via structure, and plotted against PWB lot, drill column, or via position.

This approach allows for identification of outliers caused by tool wear or board stack variation. Regions with elevated Ra values may correlate with plated copper pull-away or localized delamination when subjected to thermal cycling.

⸻

🔧 Recommendations

• Evaluate Ra and Rq from representative drilled holes on each new PWB lot.

• Use SEM or profilometry tools—optical inspection is insufficient for identifying roughness-based failure risk.

• Set internal benchmarks (e.g., Ra < 2.0 µm) for critical layers and high-reliability applications.

• Include drilled hole roughness as a QA parameter when auditing new board suppliers.

⸻

Support Available

SEM Lab Inc. now offers remote consulting services to support engineers involved in resolving product quality issues. If you’re encountering via-related failures or want to strengthen your board qualification process, I can assist by reviewing failure data and providing recommendations based on decades of laboratory experience.

📧 ehare@semlab.com

🌐 www.semlab.com

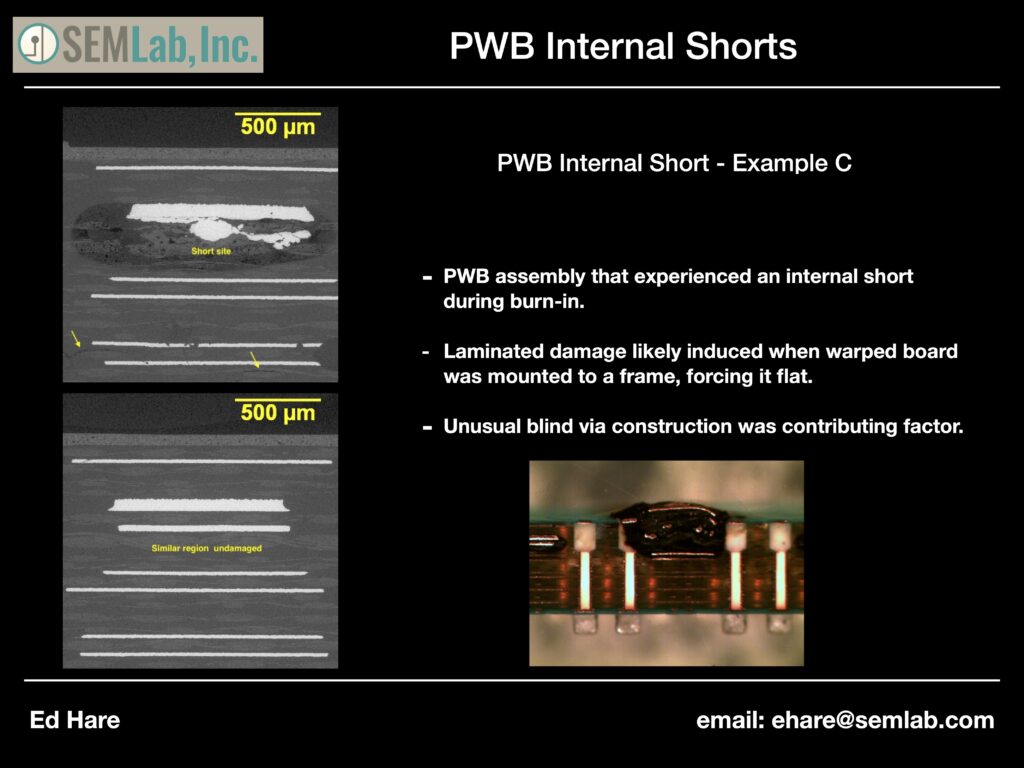

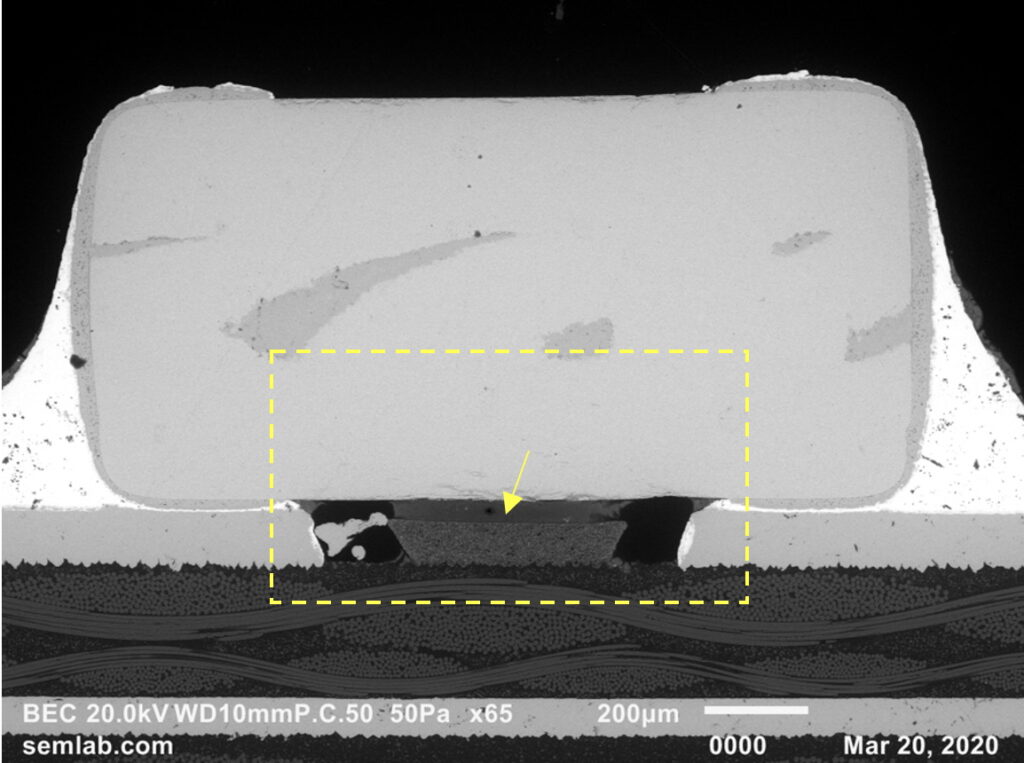

PWB Internal Short – Example C

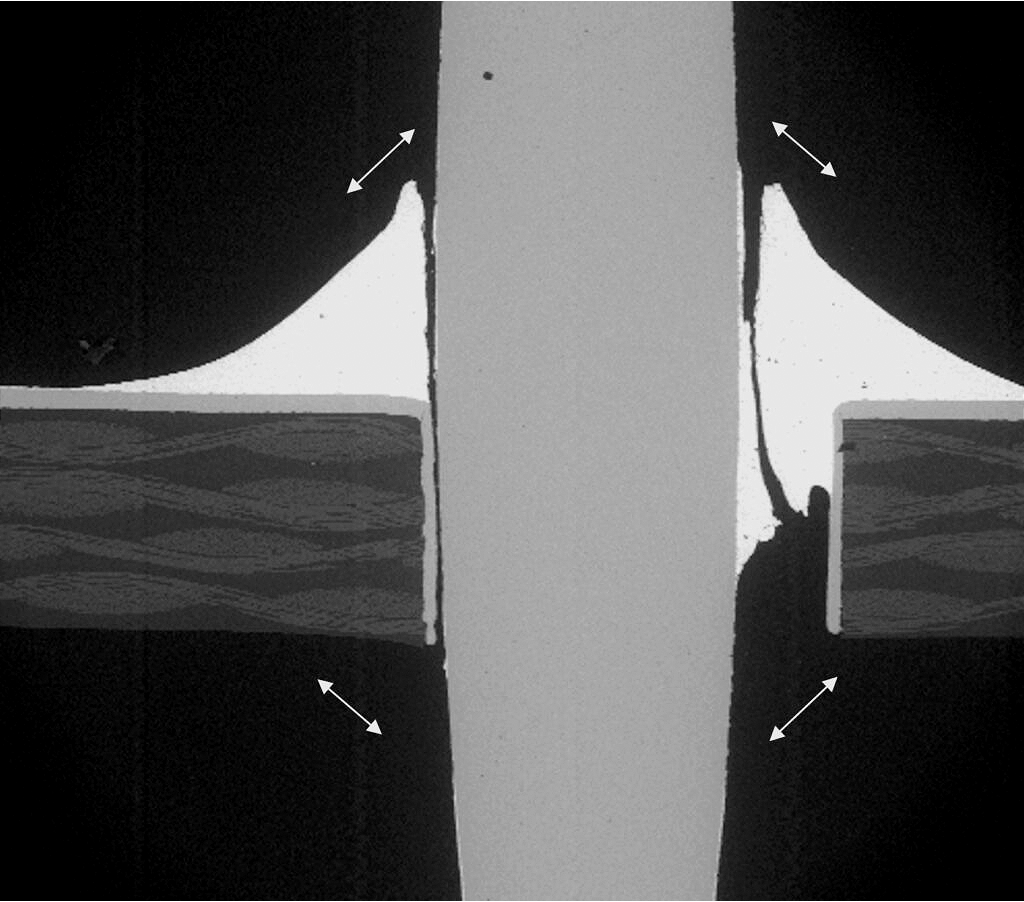

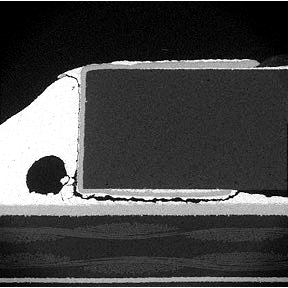

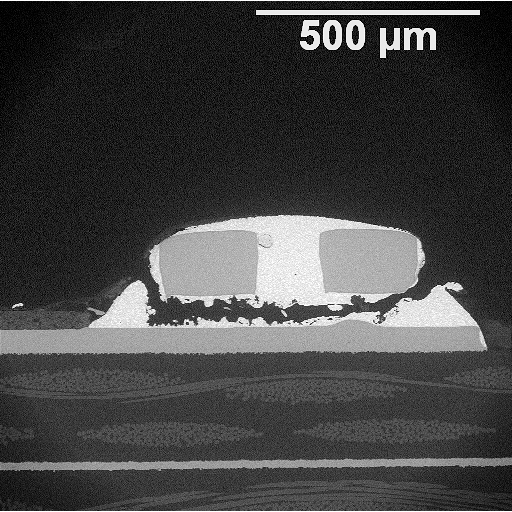

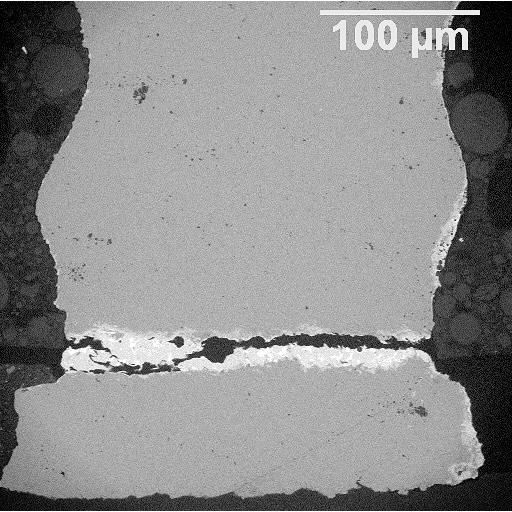

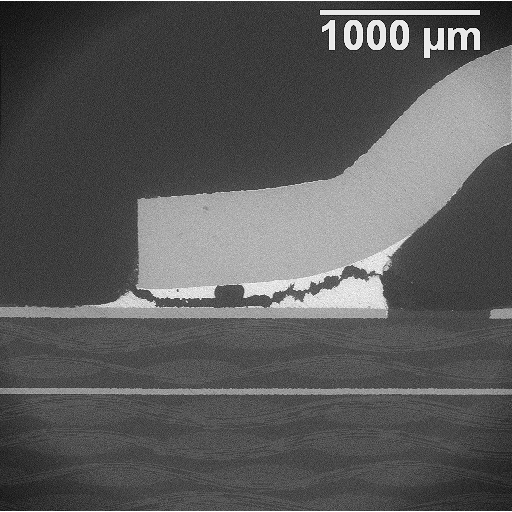

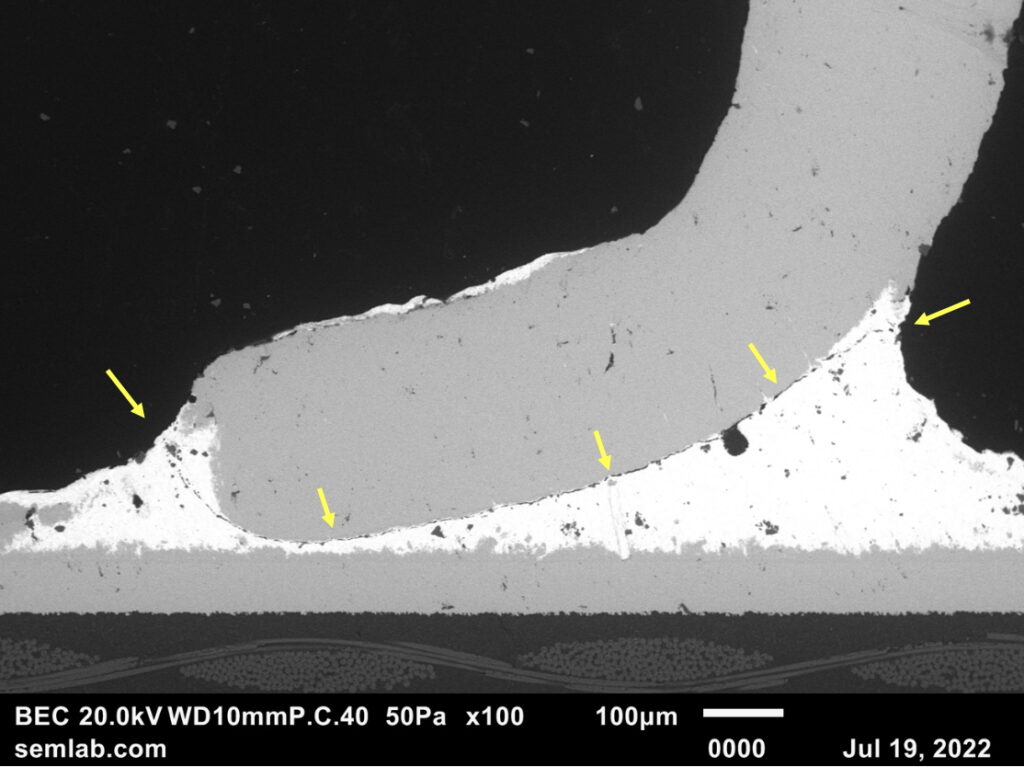

This slide presents a failure analysis case study of a printed wiring board (PWB) that developed an internal short during burn-in testing. The cross-sectional SEM images highlight localized laminated damage, which was likely caused when a warped board was forcibly mounted flat, inducing internal mechanical stress. Comparison with an undamaged region confirms the localized nature of the failure. Additionally, the use of an unusual blind via construction appears to have exacerbated the issue, contributing to the internal short.

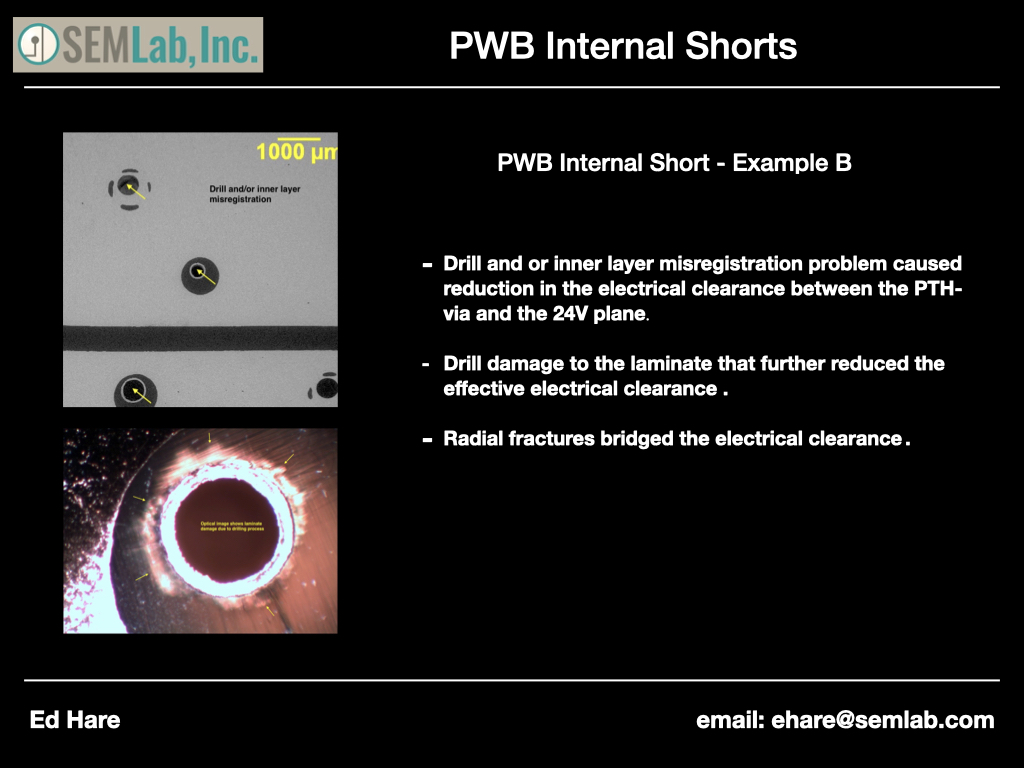

Investigating Internal Shorts in PWBs: Example B

In multilayer printed wiring boards (PWBs), internal shorts can arise from subtle but critical manufacturing defects. This case study highlights a failure mode linked to drill or inner layer misregistration, which compromised the electrical clearance between a plated through-hole (PTH) via and a 24V internal plane. The resulting drill-induced laminate damage, combined with radial cracking, facilitated an unintended electrical bridge. Through microsectional and optical analysis, we demonstrate how mechanical misalignments propagate into latent electrical reliability risks.

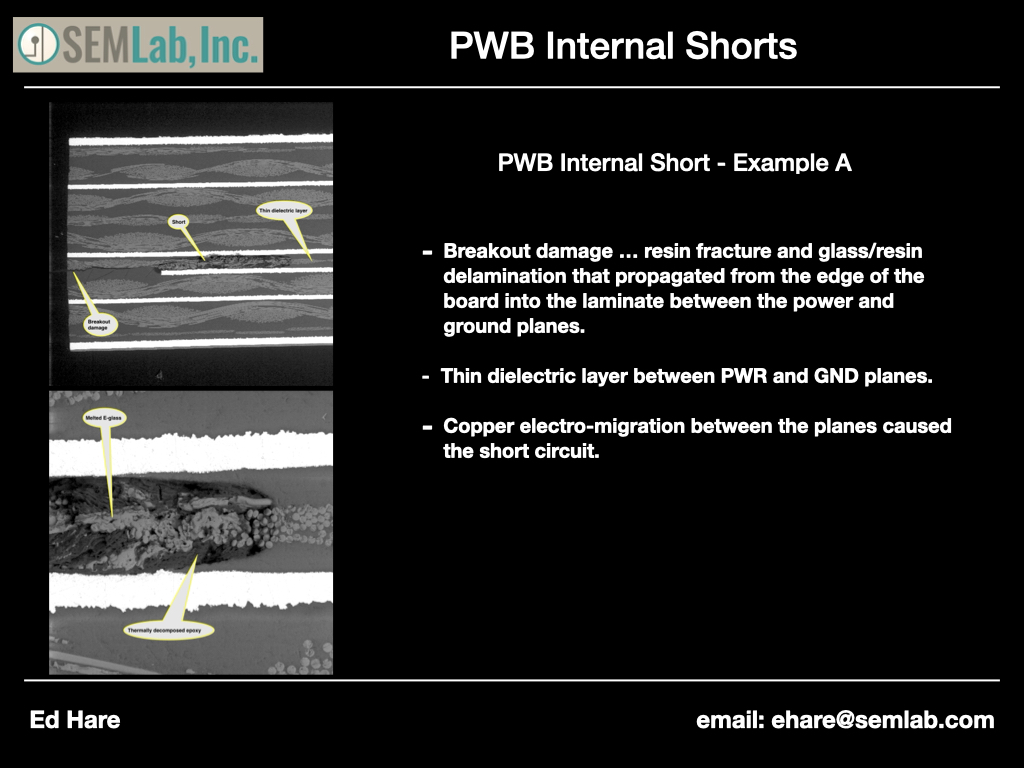

Power and ground plane shorts in multilayer PCBs can be difficult to trace, especially when the root cause lies deep within the laminate structure. This example highlights an internal short caused by resin fracture and delamination, which enabled copper electro-migration across a thin dielectric layer. Understanding failure mechanisms like this is essential for improving PCB reliability in demanding applications. #FailureAnalysis #PCBDesign #ElectroMigration #MaterialsScience

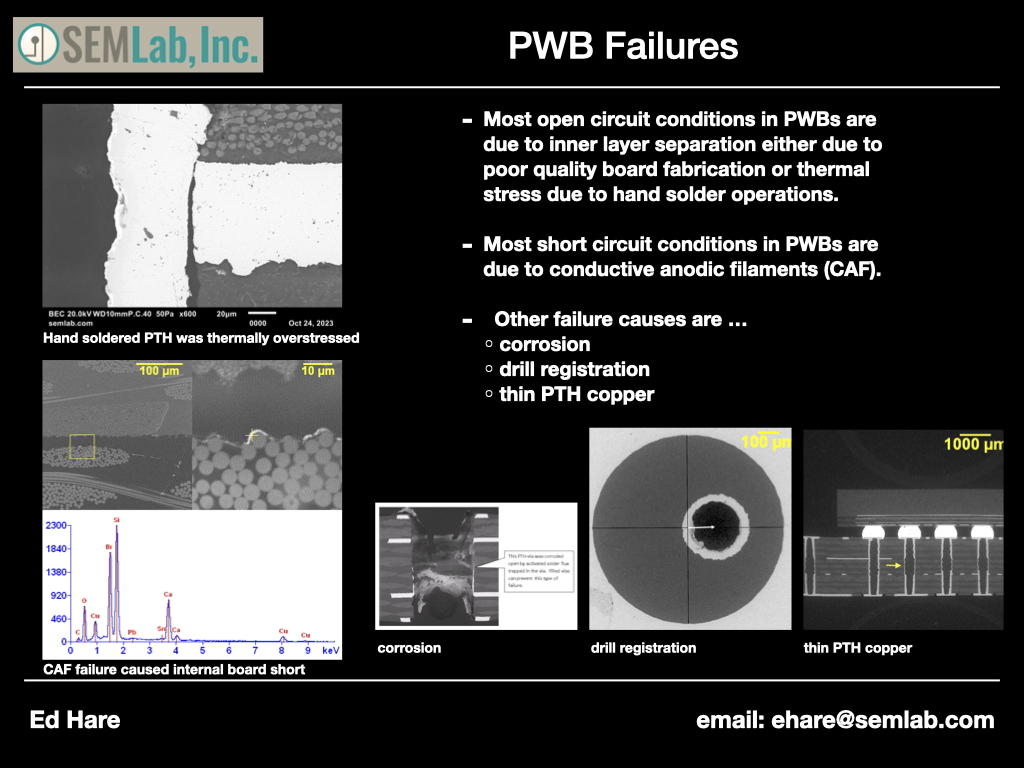

PWB Failure

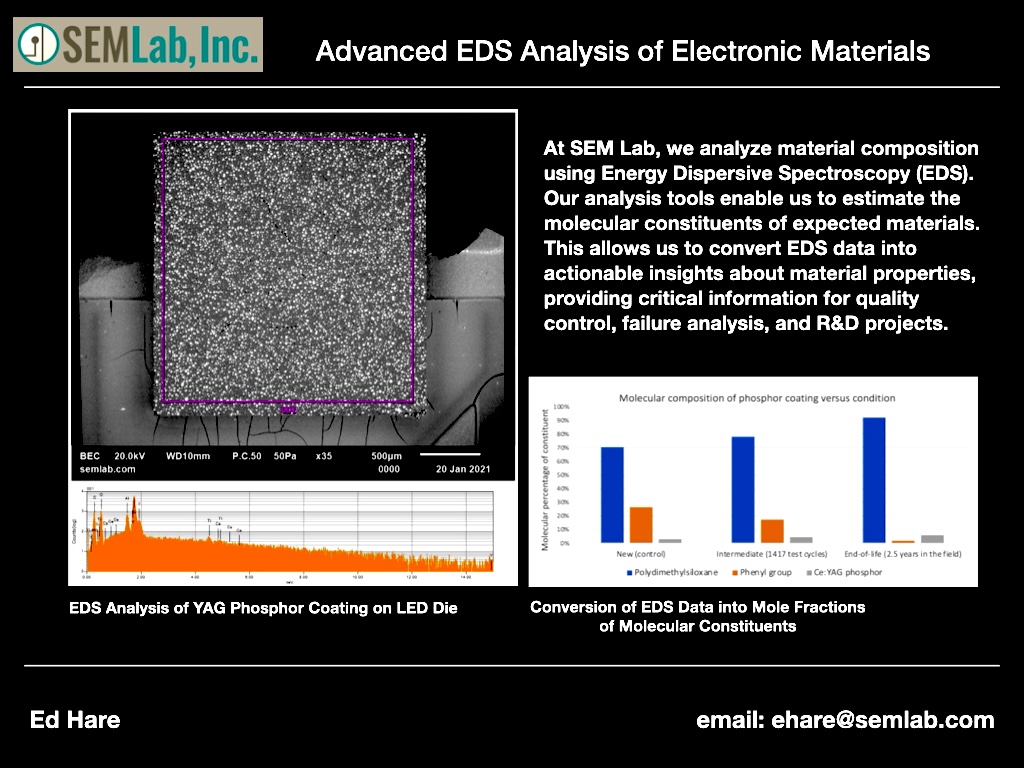

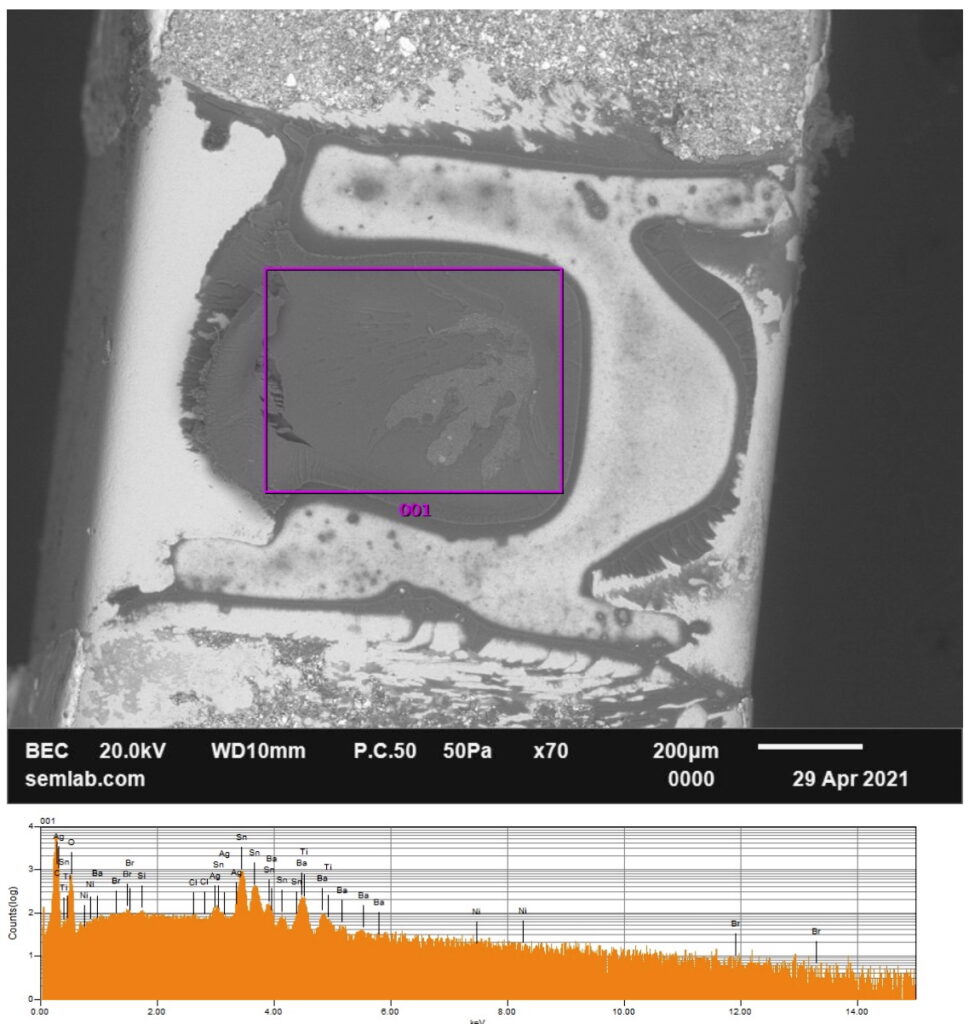

Convert EDS data into actionable insights …

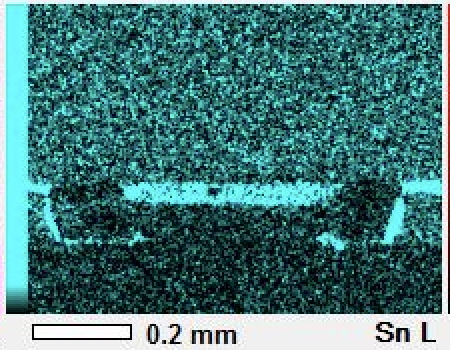

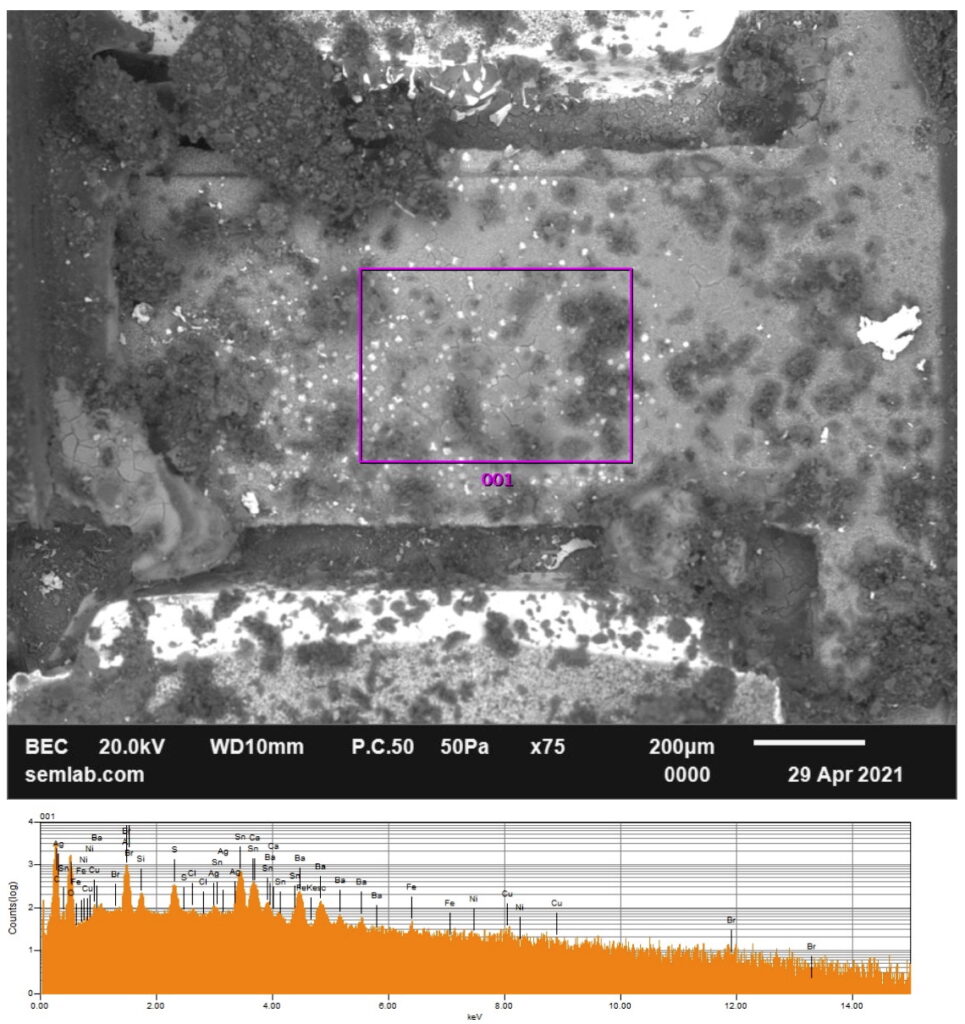

MLCC Flux Entrapment

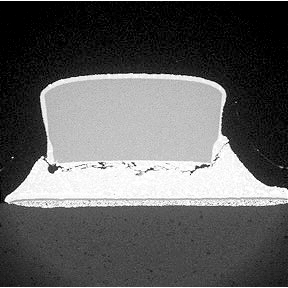

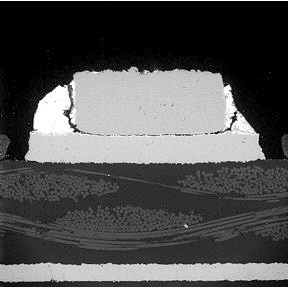

MLCC short circuit failures on PCBAs are often caused by bending fractures, where internal electromigration shorts develop between opposite electrodes along the fracture. Short circuit failures are also caused sometimes by capacitor manufacturing defects such as knit line failure, firing cracks, or dielectric porosity. But we see more frequently in recent years cases where the capacitor short is external, growing due to electrochemical migration through flux entrapped under the MLCC from terminal to terminal.

Fortunately, our primary method of examination of MLCCs is a microsection of the capacitor as mounted on the PCBA (Fig. A). This orientation is ideal for evaluation of bending fractures. It also affords us a look under the capacitor.

An EDS map for Sn (Fig. B) shows a large concentration of tin below the capacitor and above the solder mask. This indicates that an electrochemical cell existed under the capacitor allowing tin to migrate from the anode to the cathode. The PCBA was operating in a moist environment, which is a contributing factor.

A second way we can look at the problem is to mechanically excavate the solder joints and remove the capacitor from the PCBA so that residue and corrosion damage can be observed on the board surface under the capacitor (Fig. C) and on the bottom surface of the capacitor (Fig. D).

Electrochemical corrosion and electromigration can involve more than corrosion of tin, as we also see corrosion of silver, copper, and nickel plating associated with metal end caps and PWB mounting pads or from SAC305 solder.

Contamination by chlorine and bromine flux activators is common and accelerates the rate of corrosion.

This is how it works …

Even if the corrosion process doesn’t create a hard metallic short, the generation of ionic species under the capacitor can cause large enough leakage currents to generate circuit faults.

Time to failure is a function of many parameters including quantity and type of solder flux residues, operating temperature, moisture level, and electric field magnitude. The electric field becomes a significant factor as capacitor size decreases. As MLCC sizes decrease, the gap between electrodes (spacing under the component) also shrinks so that the electric field is higher.

So my question to circuit designers is …

How do you incorporate these considerations into your design rules?

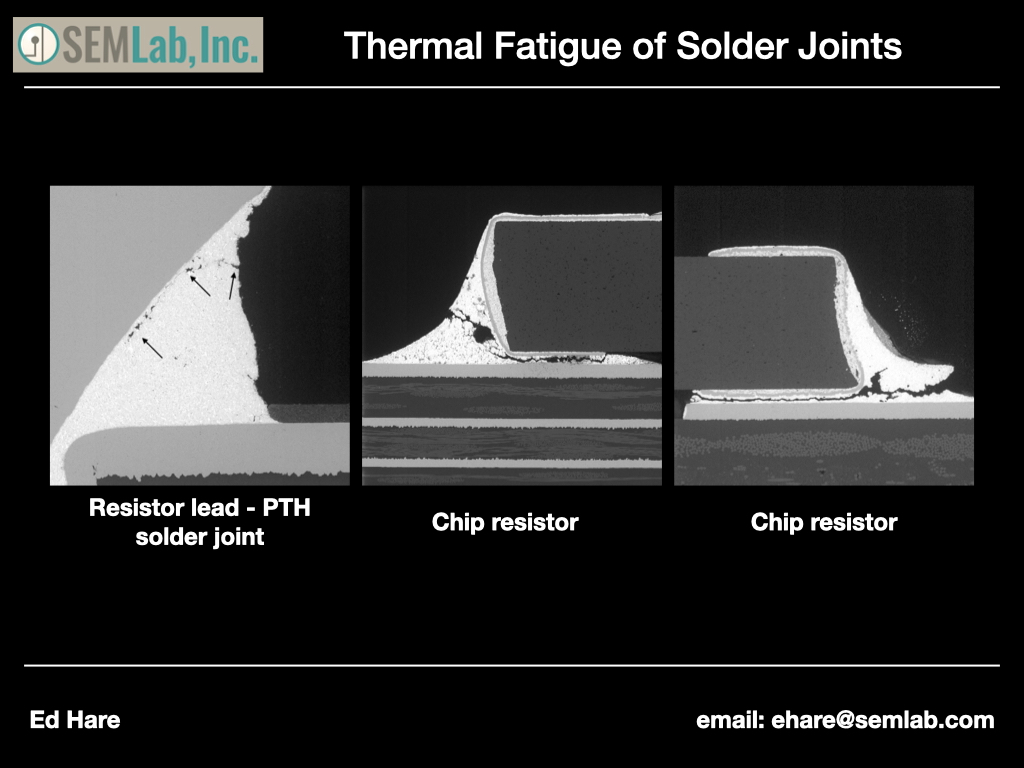

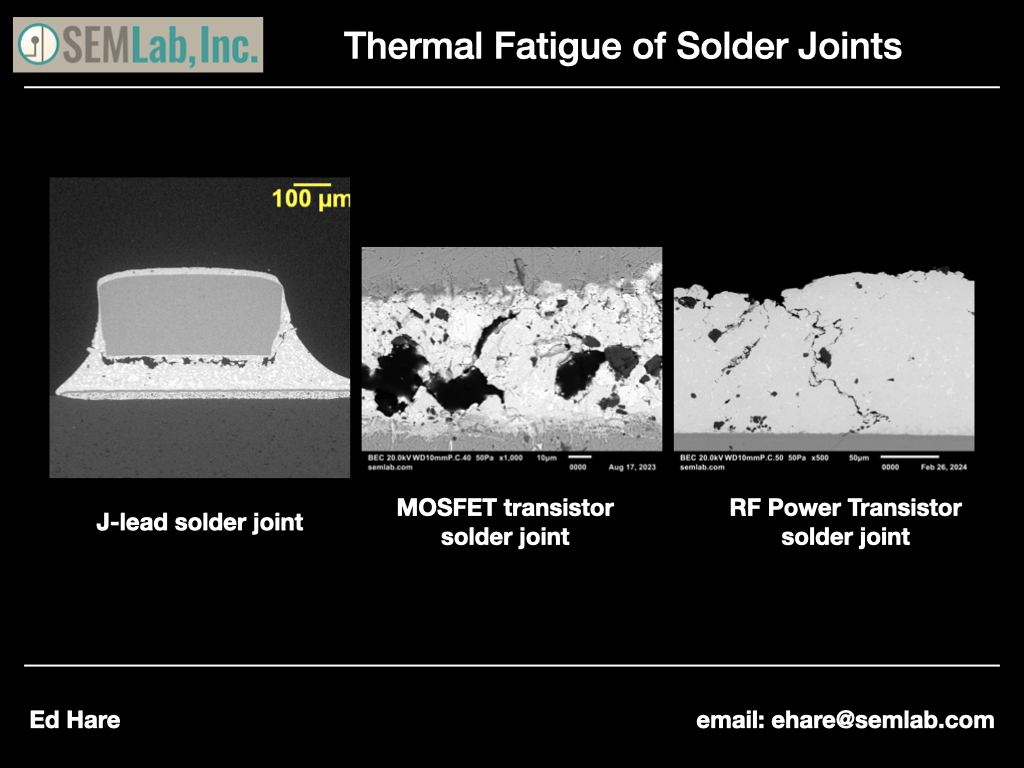

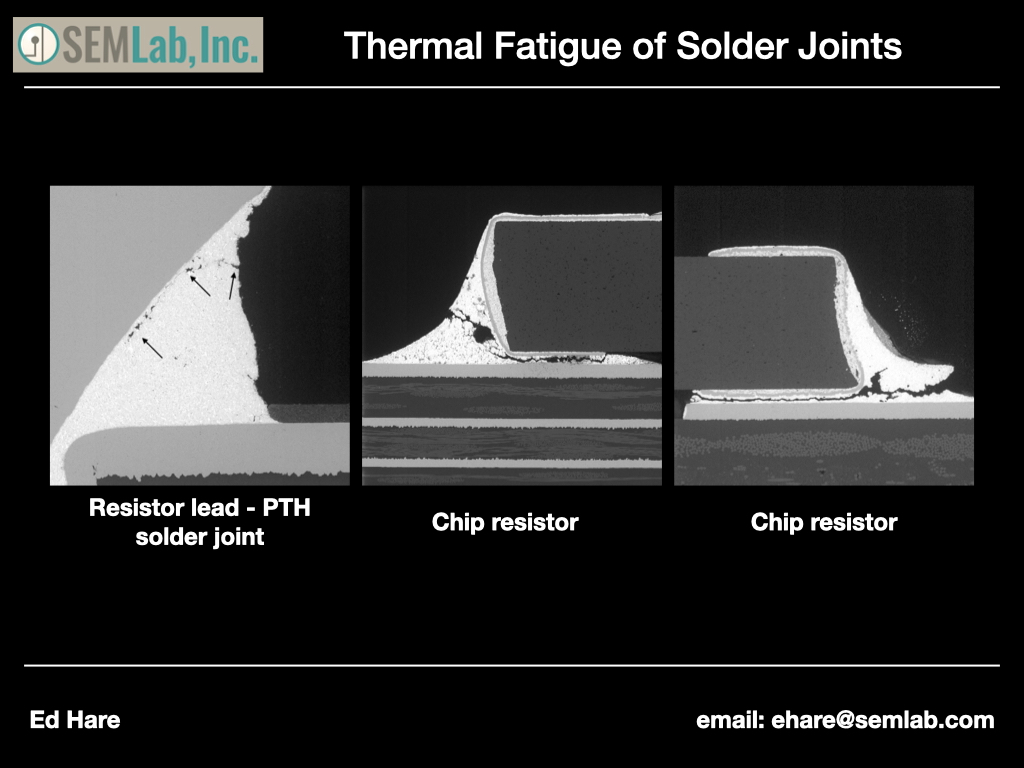

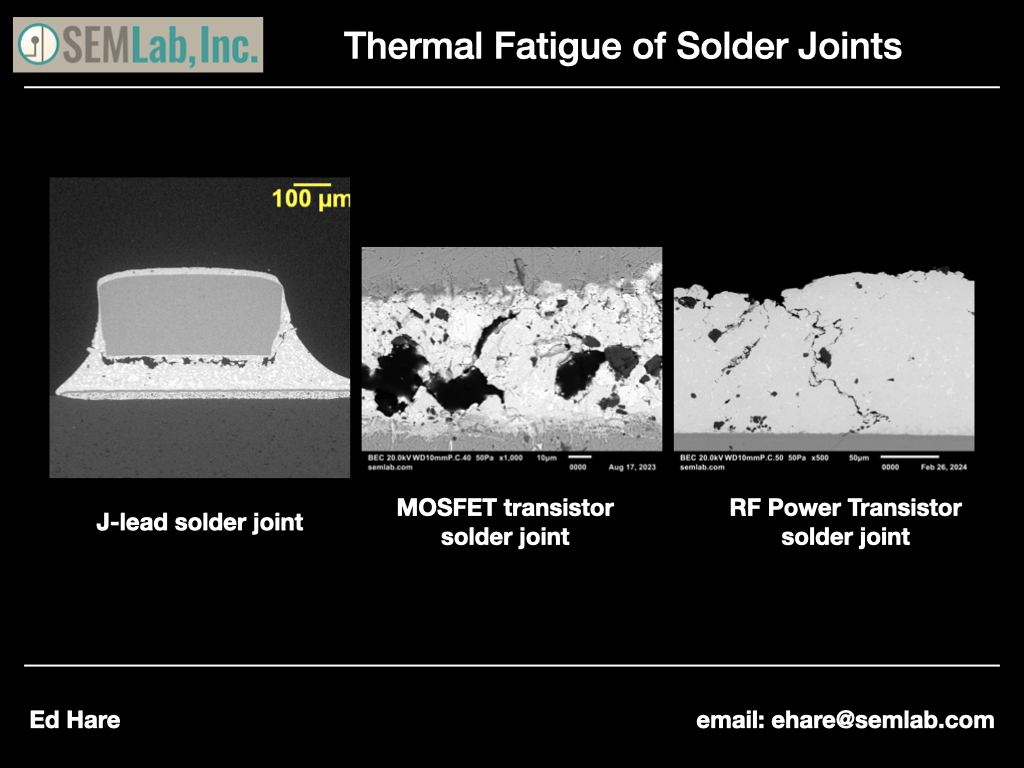

These images show the various types of fractures affecting solder joints in electronic assemblies, which includes mechanical overload failures, thermal fatigue due to coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) mismatches, gold embrittlement, creep rupture failures, and vibration fatigue fractures. Understanding these failure modes is crucial for enhancing the reliability and performance of electronic components.